Fashion and Life in the Antebellum North

Antebellum Women in Due north Carolina

Originally published as "The Five Classes of Women in North Carolina"

by Victoria E. Bynum

Reprinted with permission from the Tar Heel Inferior Historian. Fall 1996.

Tar Heel Inferior Historian Clan, NC Museum of History

By 1865 the Civil War had raged for four agonizing years, sapping the energy and resource of the South. But it was soon to cease. From April 17 to April 26, 1865, Nancy Bennett, an ordinary North Carolina farm woman, and her husband, James, provided the setting for Confederate general Joseph E. Johnston to negotiate his surrender to Wedlock general William T. Sherman.

By 1865 the Civil War had raged for four agonizing years, sapping the energy and resource of the South. But it was soon to cease. From April 17 to April 26, 1865, Nancy Bennett, an ordinary North Carolina farm woman, and her husband, James, provided the setting for Confederate general Joseph E. Johnston to negotiate his surrender to Wedlock general William T. Sherman.

Nancy and her husband owed their participation in this of import historic event to pure chance and their location near Durham's Station, between Hillsborough and Raleigh. Their "overnice subcontract," with its "oak-shaded fence" and "fine green lawn," perhaps suggested a render to antebellum "normalcy" for the state of war-weary generals. Whatever the reason, their request to see on the Bennetts' land allows us a rare glimpse into the life of an otherwise obscure farm woman and how she lived in the years before the war.

Usually, women of the wealthier planter class from this menses in history command our attention. Novels and movies provide united states with views of women in the antebellum S who are graceful, charming "belles"—attending barbecues, county fairs, and cotillion balls until matrimony transforms them into plantation mistresses.

In truth, these images are simplistic, exaggerated, and largely imaginary, and they are true for only a few women. The images ignore the experiences of African American women, and they do not speak to the realities of life for the vast majority of North Carolina's white women, either. Like Nancy Bennett, most white women were wives or daughters of nonslaveholding yeoman farmers.

Women in the Yeoman Farmer Form

Nancy Leigh Pierson was a 30-yr-erstwhile widow when she married James Bennett on May 21, 1831. Remarriage was important to women of the twenty-four hours, because unmarried women had few economic options. Like spinsters (women who never married), young widows were oftentimes forced past societal pressures and beliefs of the fourth dimension to alive with relatives.

Nancy and James began life together with few worldly appurtenances, and throughout their union, the couple struggled to become financially secure. In 1846 the Bennetts purchased, on credit, about 325 acres of land on the Hillsborough Road between Chapel Hill and Raleigh. On their farm, the Bennetts raised for themselves and for sale corn, oats, melons, Irish gaelic potatoes, and pork. Both husband and wife (and presumably, eventually children) worked in their fields, gardens, and stockyards. Considering of its location on the busy Hillsborough Road, the Bennett farm also served at times every bit a grocery store, a tailor and cobbler store, and a country inn. The Bennetts finished paying for the land in eight years.

Nancy played a crucial office in the family's economic struggle past producing vesture that she sold to the public. In improver, she occasionally operated a sort of "bed-and-breakfast" inn for travelers. While her husband sold horse feed, tobacco plugs, and liquor to guests and passersby, Nancy provided lodgers with clean bedding, supper, and breakfast—all for a profit that contributed to the family unit's income.

Sherman described the house equally "scrupulously neat, the floors scrubbed to a milky whiteness, the bed in i room very neatly made upwardly, and the few articles of furniture in the room arranged with neatness and taste." His words described good housewifery and more. Over the years, Nancy's thrift, efficiency, and, to a higher place all, difficult work were vital contributions to her family's economic success.

Women in the Poor White Class

Unlike yeoman subcontract women, who worked to support themselves or to aid in supporting their families, women in the poor white class lived in households where no belongings was owned and where economic circumstances forced them to work at jobs outside their homes even to pay rent. For case, on the Flat River in Orangish Canton, several households of older women, probably widows, and their grown or teenaged children worked at the Orangish Factory Cotton fiber Manufactory. Factories were rare in antebellum N Carolina, however—near wage-earning women labored long days in the homes or fields of their neighbors.

Women in the Planter Class

Planter women such as Lucy Martin Battle, the wife of state supreme court justice William H. Battle, frequently fulfilled two roles. Commencement, they were household managers. Lucy primarily kept accounts of the family's food and clothing supplies and planned and hosted the many social events required by people of the Battles' upper-class rank. Planter women also filled the role of plantation mistress, overseeing the labor of the enslaved persons who enabled them to fulfill their responsibilities and duties. Lucy strived to exist good to her slaves. She granted them holidays, recognized their family ties, and respected their knowledge virtually crops and livestock, which was ofttimes greater than her own.

Although upper-grade white women and enslaved women shared the same earth, their lives differed enormously. Lucy, for case, sometimes wearied of enslaved women's refusal to work at the pace she desired. Other mistresses expressed outright antipathy for their slaves. Catherine Devereux Edmondston, for case, accused hers of malingering in order to be assigned housework instead of fieldwork. She readily accepted the concept of "proper station" in life, believing that women of African descent were expected to piece of work from sunup to sundown in cotton fiber fields, while white women like herself were intended to treat dahlias, make blackberry vino, or decorate elaborate cakes for family unit celebrations.

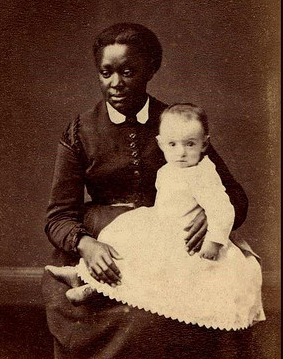

Enslaved and Free Black Women

In addition to shouldering heavy workloads, enslaved women became wives and mothers, though under vastly different circumstances than white women. N Carolina courts did non recognize slave marriages as legal, nor did they protect slave families from being broken apart by their masters.

In addition to shouldering heavy workloads, enslaved women became wives and mothers, though under vastly different circumstances than white women. N Carolina courts did non recognize slave marriages as legal, nor did they protect slave families from being broken apart by their masters.

Even in slaveholding households with humane masters, the laws of slavery created dilemmas for enslaved women. For case, Sarah, a Louisburg slave, "married" James Boon, a gratuitous black who traveled the country seeking work as a carpenter. Though she and her husband could not share a private home, Sarah'south owners permitted the couple to maintain a cabin, garden, and livestock on her chief'south plantation. These slaveholders sometimes immune Sarah to visit James on the road, and they even permitted the couple's young, enslaved son to travel the state with his free begetter.

Despite the relative generosity of Sarah's owners, the realities of slavery ultimately governed her life. She missed her married man and her son terribly during their long absences from the plantation. In a alphabetic character to James, she wrote, "Requite my dearest to my son and tell him I hope he is doing well and attends preaching regularly." In another, she expressed concern that her husband might be ill and in need of her care. Living together, she wrote, would "exist a greater prise [sic] to me than all the money you could make." Perhaps because of the difficulty of edifice a stable, intimate relationship with an enslaved woman, James eventually left Sarah and legally married a free black woman. The ease with which he did so is show of Sarah's powerlessness. That Sarah, and even her slaveholders, saw her marriage with James every bit valid meant naught in a court of law.

*At the time this article was written, Victoria E. Bynum was a professor of history at Texas State University in San Marcos, Texas.

1 January 1996 | Bynum, Victoria E.

0 Response to "Fashion and Life in the Antebellum North"

Post a Comment